Positive Reinforcement

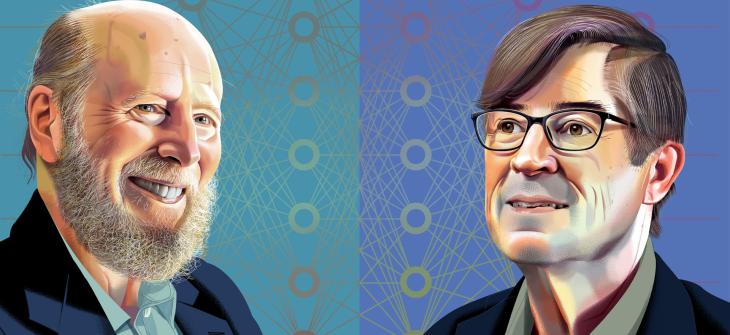

CICS Researchers Awarded the "Nobel Prize of computing"

Content

While the rest of the world was playing The Oregon Trail and using floppy disks to store data, researchers in the low-rise building of the Lederle Graduate Research Center were creating the building blocks that would someday lead us to ChatGPT. It was the late 1970s—the pre-dawn of the internet.

Inspired by reinforcement learning (RL)—the theory that the neurons in our brains seek pleasure and avoid pain—a postdoctoral researcher named Andrew Barto wondered if computers could be programmed to act in the same way. He shared this hypothesis with doctoral candidate Richard Sutton ’80MS, ’84PhD, who had arrived at UMass just a year after Barto.

Though there were early iterations of RL in electromechanical engineering, the idea quickly fell out of favor. “When we started, it was extremely unfashionable to do what we were doing,” Barto told Axios. “It had been dismissed by many people.” However, Barto and Sutton couldn’t let it go. And now, their decades of work have been recognized with the highest honor in their field—the A.M. Turing Award.

What is RL?

According to Philip Thomas ’15PhD, associate professor in the Manning College of Information and Computer Sciences (CICS) and current codirector of the Autonomous Learning Laboratory, the field of machine learning—how computers learn from data about the world—has two major branches. The first, known as supervised learning, is used to train computers on problems with known solutions. “A classic example is recognizing handwritten letters,” Thomas explains. “As humans, we know what symbols are correctly labeled as an ‘A’ or ‘B’ and so on, so we can train a computer to be more likely to produce the correct output by just shifting its decisions toward the correct response.”

Reinforcement learning, on the other hand, typically tackles more complicated problems using data that doesn’t include a “right” answer. “These are problems where we don’t know what we should do—we just know how good the outcome is,” says Thomas.

For example, Thomas’s lab is working on research to apply RL to type 1 diabetes treatment: specifically, how much insulin to inject to keep a patient’s blood glucose near a particular target level. “Having a positive outcome can be viewed as a ‘reward,’ so we’re training programs through trial and error to maximize the amount of reward the programs get and minimize the penalty, or cost,” he says. “In animals, this is called operant conditioning.”

Barto and Sutton based much of their RL algorithms on what they learned about how animals and humans learn to adapt their behavior. Perhaps the most critical contribution was the concept of temporal difference learning, which explains how our learning processes are guided by comparing the value of rewards we’re currently enjoying with the value of expected future rewards.

How is their research used in AI?

While both supervised learning and RL approaches were theorized around the same time, supervised learning quickly became the predominant approach used in computer science. Over the years, however—and through the persistent work of Barto and Sutton—RL has proven crucial for the development of AI.

Take the aforementioned ChatGPT. We can say that ChatGPT is an intelligent agent. While some information it provides to users will be established facts (e.g., the capital of Minnesota is Saint Paul) and therefore could have been programmed via a supervised learning approach, the way it responds to prompts with near-humanlike speech patterns must be learned differently. ChatGPT had to run through many iterations via trial and error and recognize when it was being rewarded for sounding more human or punished for sounding less human. So, when you ask it, “What is the capital of Minnesota?” it might say, “The capital of Minnesota is Saint Paul. However, many people mistakenly believe it is Minneapolis, the state’s largest city.”

Today, RL plays a vital role in training algorithms for many other applications, such as treating medical conditions like diabetes and sepsis via smart machines; controlling self-driving vehicles, prosthetic limbs, and a nuclear reactor; understanding the dopamine system in the human brain; targeting ads on the web; and recommending content on platforms such as YouTube, Spotify, and Netflix.

Clearly, the impact of RL has been felt across disciplines. “Barto and Sutton’s work is not a stepping stone that we have now moved on from,” said Yannis Ioannidis, president of the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), the world’s largest educational and scientific computing society. “Reinforcement learning continues to grow and offers great potential for further advances in computing and many other disciplines.”

Barto's Legacy

Andrew Barto earned a BS degree in mathematics from the University of Michigan, where he also earned his MS and PhD in computer and communication sciences. Upon graduation, he was asked to join what was then called the Department of Computer and Information Science (affectionately abbreviated as COINS) at UMass Amherst. Studying neural networks as a postdoc, Barto was surprised by how much leeway he was given to decide where his research would go. “UMass Amherst gave us the opportunity to be free ranging, exploring and pioneering the field,” he recalls. His unique position at the time required no teaching hours to fit in or white papers to publish—allowing him to devote his time fully to this research.

Though Barto has held an impressive number and variety of positions at UMass since then—including associate professor, tenured professor, and chair of the UMass Department of Computer Science from 2007 to 2011—most agree that his most significant contribution was in fostering the next generation of computer scientists. Throughout his career, he took on 27 doctoral candidates, many of whom have made their own names in the field. He has also published prolifically, and his works total over 100 papers or chapters in journals, books, and conference and workshop proceedings.

Sutton's impact

Richard Sutton attended Stanford as an undergraduate, studying behavioral psychology. He graduated in 1978 and then joined Barto at UMass Amherst, where he earned both a master’s and a doctorate in computer science. He stayed on for an additional year with Barto as a postdoc before accepting a technical staff position in the Computer and Intelligent Systems Laboratory at GTE. Though Sutton worked there for nearly a decade, UMass called him back; when he rejoined Barto for another three years, they developed many of their foundational algorithms for RL.

Sutton continued to cultivate his fascination with the way both humans and systems think as he took a position at AT&T’s Shannon Laboratory, developing AI. Sutton returned to academia and became a professor of computing science at the University of Alberta in 2003. Since then, he has been a crucial proponent in establishing Alberta as a world-renowned artificial intelligence hub. He later founded and directed the Reinforcement Learning and Artificial Intelligence Lab. In 2017, Sutton founded Knoggin AI Inc. and cofounded Google's DeepMind Alberta—the company’s first international research lab. Since 2023, Sutton has also held the role of research scientist at John Carmack’s Keen Technologies. He currently serves as the chief scientific advisor at Alberta Machine Intelligence Institute (Amii) and an AI Chair at the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR).

The highest honor

In recognition of Barto and Sutton’s work developing the conceptual and algorithmic foundations on which AI is built, the ACM honored the duo in 2024 with its annual A.M. Turing Award. Named after Alan M. Turing, the British mathematician who articulated the foundations of computing in the 1940s, the $1 million prize (funded by Google) is known in the computer science field as the “Nobel Prize of Computing.”

While Barto and Sutton will share the substantial prize money, they seem more overwhelmed by the honor itself. The morning it was announced, Barto said, “Gosh, I’m still kind of in shock. It was totally unexpected to get this award.”

Robert Manning, UMass Foundation chair and partial namesake of the Manning College of Information and Computer Sciences, shares, “As a pioneer in reinforcement learning, Professor Barto is the cornerstone of UMass Amherst’s legacy and inspiration for ensuring that AI works for the common good.”

On his X account, Sutton expressed similar awe about receiving the award: “Machines that learn from experience were explored by Alan Turing almost 80 years ago, which makes it particularly gratifying and humbling to receive an award in his name for reviving this essential but still nascent idea.”

This story was originally published in the Fall 2025 issue of UMass Magazine. Reporting contributed by Lauren Rubenstein and Daegan Miller.